After the Japanese aircraft carrier raid on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, followed by Germany’s and Italy’s declarations of war on the United States on the 11th, the three Axis navies adopted different strategies: Italy, seldom venturing out of the Mediterranean Sea, was primarily the British Royal Navy’s problem; Japan’s formidable fleet sought a buffer zone of islands and a decisive showdown with the U.S. Navy; and Germany’s Kriegsmarine was a match for neither the Royal Navy, nor the rapidly growing U.S. Navy, with the exception of its submarine service.

Based on its experience in World War I, German Adm. Karl Doenitz’s new generation of submarines, operating in well-coordinated “wolf packs,” challenged Britain’s maritime power once more. With America’s cargo ships added to their target menu, combat-experienced U-boat captains were dispatched to the Atlantic coast in Operation Paukenschlag, picking off U.S. ships with such ease that for the first half of 1942 that the Americans dubbed the waters between northeastern Virginia and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, as “Torpedo Junction.”

During that time, U-boat captains became so confident that on Feb. 28, 1942, U-578 torpedoed the destroyer Jacob Jones off Cape May, New Jersey; only 11 of its 114-man crew survived.

Not until almost two months later, on the night of April 13, did another destroyer, Roper, exact revenge in a long fight off Cape Hatteras. The German U-85 went down with all 46 hands aboard — the first German U-boat sunk by a U.S. Navy ship since America entered the conflict.

Despite that success, the expanding Battle of the Atlantic was still not going well for the U.S. Navy. As of May 8, 1942, the Germans had sunk 87 Allied merchantmen along the East Coast and the destroyer Jacob Jones, with just three U-boats lost.

The next encounter would involve a branch of American service that was, and often still is, the butt of Navy jokes: the U.S. Coast Guard. On this occasion, that image was about to change.

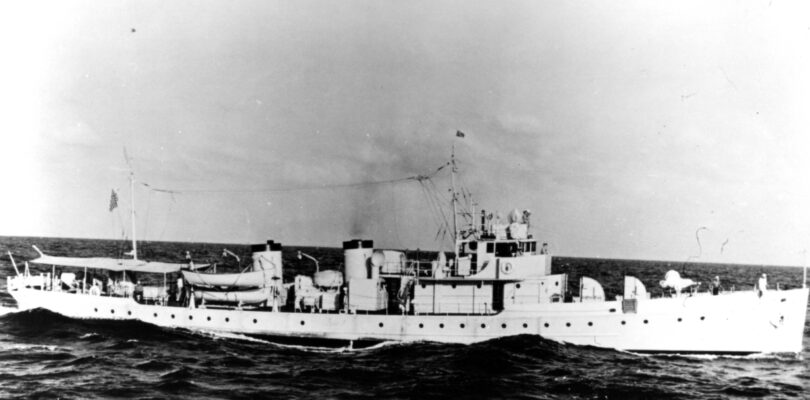

With most of the U.S. Navy’s latest warships committed to fighting the Japanese, the Coast Guard supplemented the Atlantic fleet’s arsenal with a “Bucket Brigade” comprised of all the resources it had, including the Icarus, a 1932-vintage 165-foot-long, diesel-powered “B” class cutter.

Its captain, Lt. Cmdr. Maurice David Jester, was born in Chincoteague, Virginia, on May 13, 1889. He enlisted in the Coast Guard in 1917 as a surfman stationed at Rehoboth Beach, Delaware. During the 1920s and early 1930s, he enforced Prohibition, hunting rum-runners along the eastern coast, and rose to chief boatswain’s mate in 1935. From then through to 1939, he served off California and Oregon. After the Pearl Harbor attack, he was recalled east, where he was commissioned a lieutenant and, in January 1942, received his first command, Icarus.

On May 8, Icarus left Staten Island, New York, for Key West, Florida. The following day, the vessel was zig-zagging its way off Cape Lookout, North Carolina, when the officer-on-deck called Jester to the bridge and reported their sonar man had picked up a “mushy” contact 2,000 yards off the bow in 120 feet of water. Calling all hands to battle stations, 10 minutes later Jester was positioning Icarus to attack in the general direction of the unidentified blip when an explosion erupted 200 yards off the left side — the bogie was enemy, all right, and it had beaten him to the draw.

Using his long-acquired knowledge of the region to deduce the enemy’s underwater movements, Jester fired five depth charges from his Y-guns in a diamond pattern and noted large bubbles coming up. He followed that up six minutes later with another depth charge attack, followed by two more in a “V” pattern, which produced more, bigger bubbles.

In Cape Lookout’s waters, submarine U-352 and its crew were indeed in trouble.

Although 31 years old, its captain, Hellmut Rathke had only been commanding a U-boat since Aug. 27, 1941, and as a colleague, submarine ace Erich Topp, commented in a postwar interview, “Rathke was less than the best option to command a U-boat.”

In the course of two patrols in American waters he had thus far sunk precisely nothing.

No doubt Icarus offered the prospect of sinking something, but as U-85′s fate showed, the Americans were learning and were not to be underestimated.

Rathke struck first, launching two torpedoes at the approaching the cutter, but one missed and the other exploded. Thinking it had struck the target, Rathke surfaced to survey his victim, only to see Icarus still coming on with single 3-inch cannon and 20mm guns blazing — his torpedos had detonated against the sandy bottom of Cape Lookout. Rathke ordered his boat to submerge but found himself with limited room to maneuver or dive amid a deluge of depth charges.

With U-352 too badly damaged to escape, Rathke saw no remaining alternative but to order abandon ship. As it surfaced, the sub broached, allowing the crew no exit except via the coming tower. Icarus’ crew initially thought them swarming to their 88mm gun and fired their own guns at them until Jester, observing they were not making a surface fight of it, ordered “cease fire” while U-352 went down for the last time.

As Icarus disengaged, Jester radioed the 6th Naval District in Charleston, South Carolina, with the opening precis, “Contacted submarine, destroyed same.”

Fifteen of U-352′s crew were dead, leaving 33, including Rathke, in the water. Unsure of what to do, Jester signaled Navy headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia, which advised him to just let the Germans drown. Jester, however, sought a second opinion from the 6th Naval District, which told him to go back and rescue them. Consequently, 40 to 45 minutes after the fight began, Icarus rescued 33 of U-352′s crew, whose arrival in the Charleston Navy Yard marked the first time foreign prisoners of war set foot on mainland American soil since 1815.

Awarded the Navy Cross — the first of six earned by members of the U.S. Coast Guard — Jester reserved some serious remarks for his men: “All stations were manned properly, and without confusion. Their conduct throughout was manifested with enthusiasm, alertness and devotion to duty.”

Before they parted company, U-352′s submariners made a point of thanking Jester and his men for the treatment they’d received and even after the war Rathke sent a personal letter of thanks to his former adversary.

Icarus and its sister ships of the Coast Guard would contribute much more to the Allied victory in the years to come.

Jester retired in 1944 and died of heart disease on Aug. 31, 1957. He, his wife and his son, Clarence Baynard Jester — who served in the U.S. Navy during World War II — are buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

U-352 lies where it sank in 110 feet as an artificial reef and historic site, popularly visited by scuba divers.